Homelessness

Addressing Homelessness: Housing & Healthcare

“You treat a person… you’ll win… Our job is to increase health. That means improving the quality of life, not just delaying death.”

– P. Adams and M. Mylander,

“Gesundheit!”, Oct. 1998.

Introduction

The topic of homelessness has been studied extensively over the years. Please refer to the Resources section below for selected national and Washington state-specific studies. Homelessness is a very complex subject. As such, research studies usually address sub-topics. Studies tend to focus on specific problems while ignoring the big picture. While this approach is necessary to examine specific issues in depth, we believe that one cannot ignore the overarching goals.

In our opinion, the ultimate goal is to “fix” or “solve” homelessness. In addition, we believe that government agencies, especially at the state level, often focus on specific issues and implementations without seeing the forest for the trees (so to speak). More explicitly (and based on our hands-on experience), it appears there are gaps between Washington state agency policies and what we perceive as desired healthcare outcomes. Arguably, these gaps result in significant waste, insufficient healthcare services, missed opportunities, and unsatisfactory outcomes.

Our goal is to identify and measure the gaps and influence change. We plan to do so by first proposing solutions to get people out of homelessness faster while minimizing long-term healthcare resources and costs. To get there, we are going to examine low-level “boots on the ground” data to evaluate and validate current systematic gaps. Then, we plan to compare our findings and show how other operational frameworks can improve outcomes.

How to fix homelessness

First, let’s acknowledge the fact that we cannot fix homelessness. There will always be an influx of people who become homeless. But we can certainly ding or “fix” homelessness by addressing the visible crisis and preparing solutions for the inflow of newcomers.

The key to “solving” homelessness lies in the combination of the following factors: Prevention, housing, treatment (including medical and behavioral health, i.e., mental health [MH] and substance use disorders [SUD]), and employment. This is true for all types (or sub-groups) of people experiencing homelessness (PEH): Families, youth, adults, injured workers turned homeless, and so on. Clearly, the implementation of each factor is different and must be custom-tailored for each type of homeless sub-group. But here again, we are getting lost in the trees instead of focusing on the forest.

Let us go back to the big picture. How do we “fix” homelessness? What is the overarching end goal? Seems like a simple question. We think that the answer lies in the model below, where we focus on end results and try to figure out how to get there.

In the big scheme of things, individuals can be classified as one of:

(A) Can regain employment and stability (self-sustainable or partially sustainable).

(B) Have potential to be in (A) but require long-term work to get there.

(C) Will not regain employment due to permanent impairments, age, or disabilities.

Group (A) is what we refer to as “get back on your feet”. In our experience, a person can fall under (A) only when they want to get better. If a person is not motivated and not ready for self-improvement, they fall under either (B) or (C).

It seems that existing systems often provide services without requiring accountability. While this approach may be suitable for group (C), we believe that people engage more when they are accountable, which in turn improves recovery. Engagement (and therefore more accountability) seems a necessary component for group (A) participants, as well as those transitioning from (B) to (A). Accountability can be achieved by setting clear expectations and structured steps, combined with consistent follow-throughs and support.

Proposed framework

Medabra is a healthcare research organization. So, why do we care about the big picture, housing, employment, and other factors below? Because: (1) Healthcare is an integral part of the bigger picture and must be studied in context, which is dictated by the big picture; and (2) All factors significantly impact treatment outcomes.

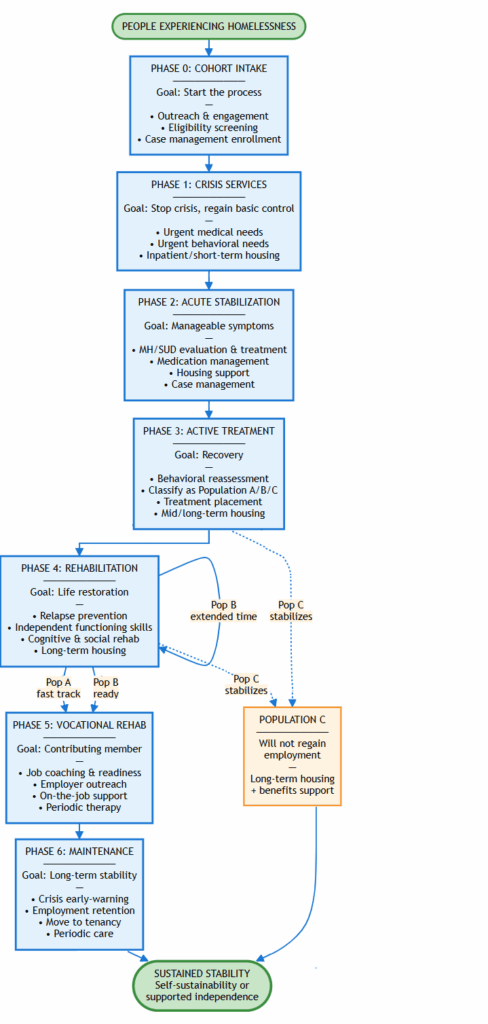

We propose the following framework to “solve” homelessness. The framework is geared towards individuals that suffer from behavioral health conditions, which is a significant portion of the homeless community. This framework will serve as the big-picture flow model as we look at the different gaps and sub-topics. It is worth noting that certain steps in the framework can be skipped or shortened as needed depending on each PEH sub-group.

Phase 0 – Cohort intake

Goal: Start the process

How: Identify a group of homeless individuals to enter the full pipeline

a. Outreach, engagement

b. Initial evaluation/screening (for housing, Medicaid, behavioral health (BH), medical conditions)

c. Enrollment into coordinated case management

Phase 1 – Crisis services

Goal: Stop crisis, regain basic control

How: Ensure immediate safety, reduce acute symptoms, prevent harm

a. Assess and attend to urgent medical needs (ED/ER), medication

b. Assess and attend to urgent behavioral needs (detox, MH urgent care), medication

c. Inpatient / short term housing

d. Initial system-entry case management (system registration, initial prep for next steps)

Phase 2 – Acute stabilization services

Goal: Predictable and manageable symptoms

How: Behavioral stabilization to enable a person to engage in treatment

a. Behavioral (MH/SUD) evaluation and treatment – detox, initial therapy

b. Continue med care, med adjustment/management

c. Inpatient or short-term housing support

d. Case management (housing planning, daily structure, basic needs, safety planning)

Phase 3 – Active treatment – triage and placement

Goal: Recovery

How: Treat the underlying mental health and/or substance use disorder

a. Behavioral (re)assessment

a.i. Evaluate MH/SUD short-term / mid-term / long-term needs

a.ii. Identify suitable MH and SUD program/treatment/placement (inpatient -> -> outpatient -> routine appointments as appropriate over time)

a.iii. Classify and revisit potential outcomes – whether a person belongs to (A), (B) or (C).

b. Continue med care, med adjustment/management

c. Housing (mid-term or long-term)

d. Ongoing case management

Phase 4 – Rehabilitation and functional recovery

Goal: From treatment to life restoration

How: Build real-world functioning and community integration

a. Continued SUD/MH – Relapse prevention

b. Restoring independent functioning, daily-living skills training

c. Cognitive rehab

d. Social skills, relationship building

e. Housing (long-term)

f. Intensive case management

Phase 5 – Vocational rehab / supported employment

Goal: Become economically self-sustaining

How: Prepare for, obtain, and maintain employment

a. Job coaching and readiness (resume building, interview skills, benefits counseling)

b. Employer outreach

c. On-the-job support, maintaining stability while working

d. Housing (long-term)

e. Continued SUD/MH – From relapse prevention to periodic therapy

f. Continued medical follow-ups

Phase 6 – Maintenance, relapse prevention

Goal: Long-term stability, prevent decompensation

How: Sustain recovery, housing, and employment

a. Crisis early-warning planning

b. Employment retention support

c. Housing (move to sustainable tenancy)

d. Continued SUD/MH – Periodic therapy

e. Continued medical follow-up

In our viewpoint, the model is designed to cover the arc: crisis → clinical recovery → functional recovery → employment → long-term maintenance. In addition, it is designed under the ultimate (eventual) goal of self-sustainability. Going back to the A/B/C populations, we have:

• A = move relatively quickly through Phases 3 → 4 → 5 → 6

• B = spend extended time in 3–4, then eventually progress to 5 and 6

• C = stabilize in 1–4 as possible, then transition to long-term housing + benefits support instead of remaining phases.

The following diagram summarized the proposed framework.

Fig. 1: Diagram depicting the framework proposed to “solve” homelessness.

Evaluating framework performance

The components of the framework are not novel. However, modeling the high-level end-goals, approach, transitions, combined with additional administrative changes (more on this below), while keeping the end-goal in mind throughout the different phases – those (we believe) are new.

The government is allocating enormous resources to tackle homelessness, and this pattern increases over time. Yet, in our opinion, the results do not exhibit long-term sustainability and improvements. Facilities and providers are stretched thin, there are never enough beds, and spending is at all-time high. Consequently, we believe that the proposed framework is important for the following reasons:

1) Homeless persons that demonstrate motivation for self-improvement, i.e., group A, can receive help to get back on their feet faster. Following the framework allows them to accelerate their independence and reduce their reliance on government systems.

2) Those who are not ready to advance to self-sustainability but have the potential to do so, i.e., members of group B, can advance through the framework. More work is needed here to understand and ensure that those in group B do not get “stuck” in the framework and eventually exit to group A or C.

3) Those who rely on social services and benefits are identified as such early in the process and are treated and housed accordingly.

Therefore, the framework allows people to reach their ultimate steady-state faster, thereby minimizing use of public resources.

Governing agencies in Washington State

Next, we would like to understand how the proposed framework translates to the status quo – what is available, what is missing, and what needs to be improved. Before diving into the details, it is important to note that Washington state homelessness and related health services are governed by the following agencies:

| Agency | Area Governed |

| WA Health Care Authority (HCA) | Medicaid/Apple Health, behavioral health, SUD/MH treatment, crisis system, Foundation Community Support (FCS) supportive housing/employment |

| Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) | Long-term care, benefits, disability determination, guardianship, aging, developmental disabilities, also – MH inpatient facilities (licensure, etc.) |

| Department of Health (DOH) | Facility licensure (inpatient/outpatient SUD facilities / BHAs, hospitals), clinical standards, provider certification |

| Department of Commerce | Homeless housing, PSH, HMIS, youth homelessness, rental assistance |

| Behavioral Health Administrative Service Organizations (BH-ASOs, e.g., Carelon) | Crisis system (hotline, mobile teams), involuntary treatment, non-Medicaid BH services, some SUD/MH for uninsured |

| Managed Care Orgs (MCOs: Molina, CHPW, United, Wellpoint, Coordinated Care) | Medicaid managed care for 96% of population: outpatient BH, SUD, hospital, Med Assisted Treatment (MAT), care management |

| Counties / Cities / Continuums of Care (CoCs) | Coordinated entry, shelters, street outreach, Rapid ReHousing (RRH), Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) |

| Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) | Health Care for the Homeless–Funded clinics (primary care, BH, SUD) |

Confused? So are we. Especially (again, from our in-field experience), considering the lack of cross-agency communications.

Current services and allowable treatment

The services required by our proposed framework are relatively well defined. Next, we wish to examine what behavioral health services are available under the Washington state agencies above. We also need to understand the constraints imposed by various federal or state agencies on facilities and services. For example, allowable length of treatment, required authorizations, billing/reimbursements, and so on. We must understand these constraints to be able to perform practical analysis to see which services or treatments fit the framework in real life.

To dig down, we started by reviewing SERI guides from the last several years. The SERI guides mention some limitations for some services and facilities but fail to provide a broad set of information. Next, we mined the HCA, DSHS, and DOH websites. We were still unable to find all the answers even though we reviewed all links and documents published on their portals. After that, we examined other sources such as the CMS guidelines, SAMHSA, ASAM, and various other sources and publications (e.g., county data). Through all those, we were able to compile the following conclusions, which are still incomplete.

All treatment is obviously based on medical necessity, which also impacts the length of stay and encounter limits. However, medical necessity doesn’t mean that MCOs actually pay facilities and providers for services. Therefore, when it comes to understanding the available services, we must keep in mind that MCO billing contracts and policies are far more dominant compared to medical necessity considerations. Similarly, certain Medicaid treatments are subject to authorization or utilization review (UR). Both authorizations and length of stay (LOS) can be contract-specific to an MCO, which is not public information.

Putting all this together, below are tables showing the information we were able to extract from different sources for the different phases of the framework, to try to understand the available facility types, programs, allowable lengths of stay for admission, readmission, and other limitations.

Crisis, withdrawal, and inpatient-ish MH facilities

| Facility / Program | Hrs per day & length of stay per episode | Source | Hard limit vs “typical”? | Notes | Phase |

| 23-Hour Crisis Relief Center (CRC) | LOS: ≤24h by statute; DOH rule allows up to 36h only if waiting for DCR or transition. | Link | Hard regulatory limit per stay; no annual cap found. No formal limit on number of visits per year. | RCW 71.24.916 + WAC 246-341-0903 / DOH rulemaking and HCA CRC fact sheet | 1 |

| Facility-based Crisis Stabilization Unit (CSU) / crisis stabilization facility | 24h per day (licensed residential setting) LOS “often 3–5 days”; crisis funding report: LOS “typically 3–14 days.” | Link | These are descriptive ranges, not binding caps. No explicit max days in rule/guides → don’t know a true legal max. | WA HCA facility-based crisis stabilization fact sheet & 2024 legislative “crisis services funding gaps” report. | 1 |

| Clinically Managed Residential Withdrawal (Sub-acute detox – H0010, medically managed H0011) | 24h per day LOS: SUD billing materials say LOS is based on medical necessity; typical detox episodes in practice are a few days, but WA doesn’t publish a specific day cap. | Link | Only clear rule: must be in facility and actively treated to bill each per-diem day. We don’t know a formal max days in WA policy. | Same for medically monitored acute detox (H0011). | 1 |

| Short-term involuntary E&T / SWMS (E&T & Secure Withdrawal Mgmt & Stabilization under ITA) | 24h per day LOS: initial 120 hours (~5 days); court may order up to 14 days additional. | Link | Hard limits for that court order stage. Longer stays move into 90/180-day commitment tracks. | Applies to E&Ts and SWMS when used for short-term involuntary under ch. 71.05 RCW; subject to court orders. | 1–2 |

| Mental Health Peer Respite Facility (H0045) | Overnight; billed per diem LOS: WAC 246-341-0725 + MH billing guide: facilities must limit services to max 7 nights in a 30-day period; billing guide says “seven days per calendar month per provider”. | Link | This is a clear hard limit: 7 nights per 30-day period per provider. | This is one of the few places you get a real numeric cap straight in rule + billing guide. | 1–2 |

| Secure Withdrawal Management & Stabilization (SWMS – H0017) | 24h per day LOS: When used involuntarily under ITA, LOS follows E&T-style rules: initial 120h, then up to 14 days by court order, then longer 90/180-day commitments. | Link | Those 120h/14d/90–180d limits are hard commitment law limits, not specific to the HCPCS code. | SWMS is also a residential SUD facility type; beyond ITA use, LOS is governed by medical necessity & contracts. | 1–2 |

Opioid Treatment Programs (OTP)

| Facility / Program | Hrs per day/week & total length of services | Source | Hard limit vs “typical”? | Notes | Phase |

| Opioid Treatment Program (methadone/buprenorphine OTP); From acute stabilization to maintenance | CMS pays weekly bundled episodes; clients may present daily, several times/week, or less often depending on take-home schedule. | Link | No limit; treatment continues as long as clinically appropriate. | The only time-related numbers in OTP policy are about take-home doses (e.g., up to 14–28 days of medication supply), not total treatment length. | 2–6 |

SUD residential / withdrawal, MH residential

| Facility / Program | Hrs per day & length of stay per episode | Source | Hard limit vs “typical”? | Notes | Phase |

| SUD Intensive Inpatient Residential (ASAM 3.5 – H0018) | 24h per day LOS: HCA / SERI / ASAM materials describe as short-term; SUD 1115 demonstration targets statewide average ~30 days residential LOS. | Link | The 30-day figure is an average target under the waiver, not a per-client cap. Don’t know a hard client-level max in WA rules. | IMD financing rules also push toward avg LOS ≤30 days; some MCO contracts may have UM rules but they’re not public. | 2 |

| 90- and 180-day civil commitment beds (community hospitals & E&Ts) | 24h per day LOS: Program explicitly covers court-mandated 90- or 180-day inpatient MH. | Link | Hard per-order length (90 or 180 days); can be renewed by court. | HCA 90/180-day civil commitment program page + toolkit. | 2–3 |

| Intensive Behavioral Health Treatment Facility (IBHTF) | 24h per day LOS: Described as “long-term program”; residents can retain their bed and return after hospitalizations <30 days. No LOS cap given. | Link | Intentionally long-term; no explicit day limit found → don’t know a hard cap. | IBHTF sits between E&T and MH Residential in intensity; financing constraints may exist but not a clear LOS rule. | 2–3 |

| Mental health residential – “short-term” (H0018) | 24h (per diem; must be in facility ≥8h for that day under SERI) LOS: HCPCS/SERI describe as short-term, “stay is typically <30 days.” | Link | “Typically <30 days” is descriptive, not a mandate. Don’t know a firm max from WA policy. | HCA state residential treatment summary notes LOS “not fixed, many programs oriented to 30–60 days,” but that’s practice, not a legal cap. | 2–3 |

| IMD psychiatric stays under MH 1115 waiver (adult SMI) | 24h per day WA MH IMD waiver: facilities must have average LOS ≤30 days and a 60-day max per client stay for which Medicaid will pay; >60 days require state-only funds. | Link | For Medicaid FFP there’s effectively a 60-day hard ceiling per stay; beyond that, it’s a financing limit, not a discharge requirement. | This applies when facility qualifies as an IMD under the SMI 1115; not all MH residential is in this bucket. | 2–3 |

| SUD Long-Term Care Residential (ASAM 3.3 – H0019) | 24h per day LOS: Defined as long-term; various WA and national docs describe residential programs oriented to 30–60+ day episodes; but no fixed cap. | Link | All the numbers here are “typical”, not regulatory. Don’t know a legal max LOS. | Some state IMD waivers elsewhere cap at 30 days; WA uses a 30-day average metric rather than a fixed per-person cap. | 3 |

| Mental health residential – “long-term” (H0019, T2048, IBHTF-adjacent) | 24h per day LOS: Defined as long-term, “stay is typically >30 days”; IBHTF doc explicitly says “long-term program.” | Link | Again, “typically >30 days” is descriptive only. Don’t know any statewide max days. | Any tighter limits are buried in specific contracts / UM policies, not in public billing guides. | 3 |

| Recovery House Residential (ASAM 3.1 – H2036) | 24h per day LOS: WA docs say LOS is based on medical necessity; separate materials show recovery houses often run 30–60+ day episodes, sometimes longer | Link | No numeric limit in WA rules/billing guides → don’t know a hard max. | Local contracts (e.g., BH-ASO provider manuals) describe LOS as driven by treatment progress/UM review, not a fixed day count. | 3-4 |

Intensive, day treatment and non-intensive outpatient treatment (SUD/MH)

| Facility / Program | Hrs per day/week & total length of services | Source | Hard limit vs “typical”? | Notes | Phase |

| MH or SUD Partial Hospitalization Program (PHP – ASAM 2.5) | Patient must need ≥20 hours/week of therapeutic services; many policies reference ~4 days/week × ≥3h/day as minimum for PHP. LOS: Neither CMS PHP policies nor WA public docs set a clear maximum number of weeks (episodes often 2–4+ weeks in practice; payable LOS unknown) | Link | So: no hard total-duration limit found → don’t know max weeks/months from official sources. | CMS LCDs + Medicare.gov spell out intensity but not episode caps; Medicaid often follows “medical necessity” + UM review. | 2–3 |

| SUD Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP – ASAM 2.1) | 9–12 hours/week; typically spread over 3–5 days/week. LOS: Up to 90 days (for standard IOP; separate specs under DUI/deferred prosecution). | Link | That “up to 90 days” appears as a policy limit for standard Medicaid-funded SUD IOP. | This is one of the clearest WA numeric caps outside peer respite. | 3–4 |

| MH Intensive Outpatient (IOP) | ASAM / Medicaid guidance: typically 9–12 hours/week, e.g., 3 days/week × 3–4h. LOS: I haven’t found a WA-specific “max days” rule for MH IOP like the SUD IOP 90-day language. | Link | Don’t know any formal episode-length cap for MH IOP in WA. Likely same as SUD IOP, which would be the case with co-occuring disorders. | Plans likely use medical-necessity + utilization management; not published as a simple day number. | 3–4 |

| SUD outpatient treatment (ASAM 1.0) – non-residential clinic | Typically 1–3h per session, few times per week LOS: Per medical necessity. Parity prohibits cap limit. | Link | WA guidance and SERI specify time per session & units but not total weeks/months caps. Medical necessity governs. | ASAM and MACPAC describe outpatient as ongoing as needed; limits, if any, come from plan UM. | 3-6 |

| MH Outpatient Treatment (Standard Outpatient Therapy / Psychiatry) | Per CPT code (30–60+ min) LOS: Per medical necessity. Parity prohibits cap limit. | WA guidance and SERI specify time per session & units but not total weeks/months caps. Medical necessity governs. | Ongoing as needed; limits, if any, come from plan UM. | 3–6 |

In conclusion, it appears that Washington state has individual behavioral health services that fit across the entire framework. However, the fragmentation between different agencies and the plethora of data sources and information easily leads to unnecessary complexities. The tables above demonstrate some of the difficulties in finding clarity around utilization, reimbursements, and limitations, which naturally translate to gaps in coordination, patient transitions, and capacity planning.

Medical facilities and services

For medical services, below are the list of relevant facilities and services. The list does not include specialized services such as dialysis, dental treatment, and the like. The list below reflects facilities and services as they relate to Medicaid / Apple Health. In addition, medical services in phases 2-4 can sometimes be provided by medical providers working in behavioral facilities.

| Facility / Services | Hrs per day & length of stay per episode | Hard limit vs “typical”? | Notes | Source | Phase |

| Hospital Emergency Department (ED) / 24/7 emergency stabilization, triage, short-term treatment | 2–24 hours typical | As medically necessary | Outpatient & inpatient hospital billing guidance covers ED without numeric caps | Link | 0–1 |

| Hospital observation services (outpatient) / Short-term monitoring, diagnostics before inpatient decision | <48h typical | As medically necessary | Observation listed as outpatient hospital service without LOS cap | Link | 0–1 |

| Urgent care / walk-in / Episodic non-emergent care | Short visits | As medically necessary | MCO benefit grids show UC covered with no numeric caps | Link | 0–3 |

| Acute inpatient hospital (medical/surgical/ICU) / Inpatient medical/surgical management | 24h care | As medically necessary | Hospital services defined in WAC 182-550; no inpatient LOS caps | Link | 1–2 |

| Nursing Facility / Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF) / Post-acute rehab or long-term nursing care | 24h care | Program-specific limits (e.g., ≤29 days for non-LTC clients) | NF billing guide describes ≥29-day distinction; no universal LOS limit | Link | 1–3 |

| Medical Respite (HRSN demonstration) / Short-term recuperative care for homeless clients with medical needs | 24/7 bed & clinical check-ins, 90-day limit per stay | 180-day total limit, hard limit (WAC 182-565-0370) | WAC specifies 90 consecutive days, 180-day max | Link | 1–3 |

| Primary care clinics / General medical care & chronic disease management | 15–40m visits | As medically necessary | Primary care covered broadly with no visit cap stated | Link | 1–6 |

| FQHCs / Community health clinics / Safety-net primary care & specialty services | Clinic encounters | FQHC encounter billing has no annual visit cap | 1–6 | ||

| Outpatient specialty clinics / Medical specialty evaluation & treatment | 20–60m visits | As medically necessary | Specialty physician services covered; no statewide caps | 1–6 | |

| Public health clinics (TB/STD/HIV) / Targeted communicable disease management | Episodic visits | Program-specific | Public health clinics operate via mixed funding with no Apple Health LOS caps | Link | 1–6 |

| Home health – acute care / Skilled nursing & therapies in home | Intermittent visits | No explicit rules except EMO-specific limits | Home health defined as short-term acute; no numeric cap in standard program | Link | 2–6 |

| Outpatient rehabilitation – PT/OT/ST / Therapeutic rehab in clinic or outpatient hospital | 30–60m, 1–3x/wk | Annual utilization limits (units/year) and PA rules | Unit-based limits exist; exact numbers vary in guide | Link | 2–6 |

| Hospice / End-of-life interdisciplinary care | Varies by hospice level | Hospice program document explains election periods, not numeric limits | Link | 2–6 |

It is worth noting that we also prepared list of facilities and programs (including their known limitations) for housing, rehabilitation, vocation rehabilitation, and other stages of the proposed framework. Especially those facilities and programs in Phase 4 through Phase 6. These lists are omitted here as we try to focus on healthcare and treatment challenges.

Systematic gaps impeding recovery

Gaps in coordination

As previously mentioned, the proposed homelessness recovery process comprises housing, medical and behavioral treatment, functional rehab, and vocational rehab / supportive employment.

For patients, the most obvious gaps lie in transitions. When an individual approaches the completion of one service, there are no obvious paths for moving to the next step. The same can be said in the event of patient regression, i.e., transitioning back to previous steps.

The next set of obvious gaps lies in coordination of services during one stage of recovery. At minimum, every stage requires appropriate housing solutions, case management (which can help housing), peer support, etc.. The coordination of services is very challenging. Often, coordination services do not exist in treatment facilities. When they are available, they only provide solutions for some (but not all) patient needs.

Gaps in services

Different government agencies oversee certain aspects of the recovery process. Yet, all factors mentioned above are required to advance treatment and minimize the likelihood of regression, decline, or relapses. In addition, it appears that certain treatment services are not as well-defined as they should be under Medicaid. Usually, when this happens, it means that there are no healthcare providers or facilities to actually perform the work.

For example, if we look at Phase 1, we can’t find Medicaid rules around street medical stabilization, field intoxication management, and other activities that combine outreach and treatment. Similarly, Medicaid is missing information about facilities/treatment-services operating between “street” and crisis/ED (e.g., non-clinical 12–24h sobering centers, safe-use monitoring sites, pre-crisis diversion hubs, etc.).

In Phase 2, for example, we are missing subacute medical inpatient solutions for those leaving the ED. If you consider the transition from Phase 2 and on, e.g., from ASAM 3.5 to 3.3 to 3.1 to PHP/IOP, then there are no clear guidelines (general requirements, funding, and otherwise) from Medicaid. And so on. However, we believe that the root cause for these and other gaps lies in missing administration components.

Gaps in administration

To explain the challenges in administration, we find it useful to draw parallels to the workers’ compensation ecosystem. If you suffer a work injury in Washington state, you start the process by going to a hospital or a primary care provider (or other providers). They know exactly how to get you into “the system”. Once you have a workers’ compensation claim, then the following administrative resources are available to you: (1) LNI is the single agency that oversees your situation; (2) Your Attending Provider (AP) orchestrates the treatment throughout your claim from A to Z; and (3) An LNI Claims Manager (CM) handles the entire process of administering your claim – from benefits to case management during treatment, through vocational coordination and your return-to-work.

If you are a homeless person wanting to get better – where do you go? Where do you start the recovery process?

The amounts and resources (money and otherwise) that Washington state spends on one workers’ compensation claim is a fraction of the cost/resources spent on a homeless person going through the revolving door of treatment facilities. So, why isn’t there a single agency governing homeless recovery? Why isn’t there a Unified Recovery Coordinator role to oversee the recovery process?

Today, homeless people can approach outreach workers or local PATH teams for help. They can also use the services of coordinated entry navigators to handle housing issues. Alternatively, they can get help from case managers working for MH/SUD facilities or hospitals for certain issues. Then there are MCO care managers, FCS specialists, and others (e.g., DVR counselors) who try to help. There is no unified or consistent tracking, transition monitoring, or coordination.

We believe that a single governing agency is necessary to tackle homelessness: One agency to oversee it all. This is lacking both at the Federal and the State level. We also think that such an agency should employ Unified Recovery Coordinators. Otherwise, at the very least, there should be a single caseworker (or the like) to orchestrate all recovery aspects and transitions, including coordination of surrounding services and benefits. That single person also serves as the go-to person for any matter during the recovery process.

Research topics and discussion

Our initial research focuses on transitions within the healthcare system. We want to understand how time is spent (1) in facilities and program; and (2) between programs. We plan to use this information to try and answer the following high-level research questions. Furthermore, we plan to dig into specific phases in the recovery process as well as clinical topics. Additional details are provided towards the end of this write-up.

Are homeless people getting better? And in what rates?

We already know how to measure improvements for those with medical, SUD and MH conditions. Here, we plan to examine claim/encounter data to identify homeless patients, measure the percentage of the population that uses healthcare services, and find out the portion of the population that demonstrates improvement. More importantly, we want to examine if patients are getting “better” in the meaning of groups (A), (B) and (C) – are they advancing in the right direction and at what pace.

For those that do, we plan to measure the time to progress and evaluate the social detriments of health (SDOH) impacting their advancement rates. In parallel, we plan to investigate what portion of the population is “stuck” in never-ending services cycles (from the ED to the street or the shelter, back to ED, to 90-day inpatient, then to the street, back the ED, etc.). Once identified, we plan to study patient patterns that will help us break this cycle and set them on a path that follows the proposed framework. As part of the work, we plan to look at the costs incurred by the system that could have been avoided and/or put to more effective use in treatment.

In the process above, we plan to use segmentation and clustering to draw geographic and community-specific conclusions applicable to Washington state. The same goes for all other research topics we describe below.

Medicaid policies versus practical needs: Where do we need Apple Health revisions or clarifications?

There are various Medicaid limitations on admission, length of stay, acceptable duration of admission/episode, readmission, and annual limits on services. There are also MCO-specific hurdles such as authorization, reimbursement, and the MCO’s interpretation and implementation of Medicaid rules.

In the first topics, we measure the length of stay and whether patients improve. Here, we plan to investigate whether the limitations imposed by Apple Health (and MCOs) are practical. What impact do Medicaid/MCO constraints impose on patients and clinical improvement? Can we identify misalignments between programs and Medicaid rules? What can we do to influence changes to the WAC or MCO payment policies where needed?

Do current transitions between facilities and program work as they should?

A key goal is to measure the gaps we mentioned earlier. One obvious gap, i.e., “low hanging fruit”, is the patient experience when transitioning between different facilities and programs. How much time is spent in transitions? What happened during the transition? What percentage of transitions are successful versus ones resulting in regression/relapse? More explicitly, we plan to look at the time spent and treatment received in facilities. Then, we wish to examine the epochs and treatment occurrences between facilities and between stages of the recovery. On that basis, we plan to identify shortfalls and areas for improvement.

Where are the bottlenecks? How can we improve capacity planning and resource allocations?

It would be very beneficial to know how many facilities, programs, providers, and of what types, are needed to serve in certain communities (and overall). We can measure and anticipate capacity needs by extracting the data and conclusions form the topics above.

Can we identify when patients are motivated? Or when are they ready for self-improvement?

If we look at the journey for patients that demonstrate improvement in recovery – what can we learn about key milestones? Can we deduct the epoch of self-motivation and self-improvement? If we correlate this information across multiple participants from a sample sub-population, can we find consistent repeatable patterns? Might we be able to synthesize the process to get patients to the point of self-motivation? What can we learn?

When should PEH enter recovery or Phase 0 of the framework?

We reviewed many publications that measure PEH sub-groups and report a snapshot of their performance (including treatment outcomes) and status-quo. However, data showing changes such as transitioning from “low service use” to “high acuity” is lacking.

We know how to extract the information from claim data. As part of our work, we plan to use the data to characterize worsening conditions, patient improvements, and other noticeable shifts. On the basis of these patterns, we believe it is possible to plan for interventions in preparation to enter PEH into recovery.

When should PEH enter recovery or Phase 0 of the framework?

If we look at address information and other details in claims to learn about patient housing situations, are housing solutions aligned with the framework goals? Can we identify patterns of treatment progress versus housing available to patients? What percentage of patients receive inpatient treatment? How is non-residential treatment progressing for those with other shelter or housing solutions?

Homelessness in data

Categorizing PEHs

The topic of homelessness encapsulates many moving parts. In order to perform any meaningful work, we have to find our niche and focus area. To wrap our heads around some of the complexities, consider the following approaches that categorize different types of PEH in federal resources.

Shelters measure the pattern of visits/stays and categorize homeless individuals as: Transitional (one or few brief stays) vs episodic (recurrent stays) vs chronic (longer stays). Chronic homelessness also has a disability component, as defined by HUD.

The US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) classifies homelessness types under the Homeless Assistance Act and the Continuity of Care program (CoC, Title 24 CFR 578). Categories in this context are literally homeless vs imminent risk vs fleeing domestic violence (DV) vs youth/families under other statutes. The HUD website provides additional information about these homelessness classifications.

The US Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) combines some of the above with housing and care needs/placement considerations: families vs single adults; chronic/high-acuity (serious mental illness or substance use disorder [SUD], disabling conditions); youth; DV survivors. These categories are used to match people with services such as Rapid Re-Housing (RRH) or Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) programs, vouchers, and so on.

We want to focus on Washington state. In Washington, the classification of homelessness is mainly driven by the Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) and the Department of Commerce. More explicitly:

Commerce published a comprehensive and important report in 2024 titled “Homelessness in Washington”. The report touches on homelessness and categorizes the population in many different facets, especially housing (who is housed vs unsheltered, and what type of housing), and then youth vs adults vs families.

For us, the most interesting classification of PEH appeared in a recent report by Washington state DSHS compiled Apple Health data in correlation with other data sources such as arrests and criminal records. The publication is titled “Changing Support Needs Among Adults Experiencing Homelessness: Washington State Apple Health Clients, 2019-2023”. The report looks at homeless adults and healthcare system utilizations and further divides the adult sub-population into low service use vs health-care needs (SUD, one or more chronic health conditions) vs primary mental illness (measured through mental health [MH] treatment) vs significant care needs. The report also calls out a category of criminal legal involvementand its correlation to health services. This classification seems to be the closest and most relevant to our study.

As a side note, we strongly encourage readers to review the works published by WA-DSHS on the subject of homelessness: https://www.dshs.wa.gov/rda-publication-categories/homelessness

Data sources and correlations

As the project evolves, we plan to broaden our partnerships and look at multiple data sources to broaden our research. These include not only claim data but also death records, and HMIS systems. Through partnerships, we also intend to integrate with EHR systems in large healthcare organizations that are known to treat unhoused clients. Additional data inputs will include law-enforcement and legal sources such as arrest and criminal records. Finally, we will look at obtaining data extracts from systems such as the DSHS Integrated Client Databases (ICDB), and others, as appropriate.

Mining claim data: Observations, analysis, and actions

Many research publications provide instructions on how to use claim and encounter data to identify homelessness. We plan to use Medicaid claims in combination with other sources to identify data points and extract relevant conclusions towards our goals. For example, to identify homelessness, we can use combinations of ICD diagnosis codes, address data, utilization patterns, and others. We can identify homelessness through the following entries and others:

1. ICD codes Z59xx (when available) explicitly tell us about homelessness status

2. ICD codes showing cooccurrence (in combination with other factors)

3. Place of service of provider type in the claim header suggesting healthcare facility for the homeless

4. ProviderOne taxonomy or NPI taxonomy suggesting a community health center

5. Billing and service patterns, encounter types and frequencies – Repeated Emergency Department (ED) or Emergency Unit (EU) visits, behavioral health crisis stabilization, detox services without follow-up PCP care, etc.

6. Eligibility data through eligibility type or aid code values (e.g., transitional housing)

7. History of MH/SUD facility admissions, discharges indicating patient left against medical advice

8. Various diagnosis upon admission correlated with recent and longer history

9. And of course – Address information – frequent change of address, POBox used by social service agencies, using known facilities such as shelters as the person’s address, missing address, “unknown” or “homeless” in address, and so on.

Broadening research coverage and interests

On top of the high-level topics listed above, we wish to keep track of various notes and topics that we want to tackle while looking at claim data. The topics below come directly as research requests from providers that work with PEH on a daily basis.

Clinical viewpoint: Treatment patterns and effectiveness

While claim data does not contain detailed provider notes, we can still derive many conclusions from looking at the data. Below are some examples:

1. When can we tell by looking at the top ~5 diagnosis that are treated in each visit? Are visits predominantly medical or behavioral? What are the most frequent complaints and the nature of those complaints?

2. If we look at diagnosis codes – has the same code been consistent over time? Have there been more diagnoses added? Have different diagnoses been refined or added over time (e.g., months or years)? What trends can we identify and what can we conclude?

Based on WA-DSHS research publication and other sources, we know that homeless clients are ~3-4x more likely to have depression diagnosis code compared with housed Apple Health clients. What can we tell by taking a closer look?

3. If someone is being seen frequently (e.g., every month or so) for depression – it is very likely that this person is non-stabilized. However, if a person is being seen (say) once every ~6 months for depression, then they are likely not at a high-risk level. We can look at other data points to support the likelihood of our assumption.

4. If we look at ICD codes 32.X, 33.X or 34.X, we can measure the severity of the depression. In addition, we can learn about comorbidities by looking at ICD codes such as co-occurring anxiety (F41.x), substance use (F1x.x), suicidal ideation (R45.851). These imply higher acuity and risk of relapse.

5. What is the frequency of admission/encounters and in what type of facilities? ED/EU? Can we identify 2 or more inpatient psychiatric admissions or crisis stabilization encounters per year?

6. What can we learn by looking at medications? Can we identify when a person was referred to Esketamine therapy? Or different type of outpatient therapy that is more specific to depression? These also tend to indicate cases of treatment resistant depression. Can we look at antidepressant classes, augmentation with antipsychotics or mood stabilizers? Can we spot continuous antidepressant fills > ~12 months? This, for example, will suggest chronic or severe conditions.

7. What can we learn from transition and changes over time? Not only changes in diagnoses and medication, but also visits to different facilities and programs (e.g., outpatient vs inpatient vs ECT, etc.). What can we learn about evolving conditions and their severity?

Open-ended topics

Finally, we plan to try to answer the following questions:

1. What % of Medicaid enrollees are homeless? There are online DSHS resources that share this information. We would like to validate the findings.

2. We regularly hear that homeless people are being moved to various cities and counties for various reasons. For example, some incarceration institutions release people directly to certain areas in Pierce County, intentionally (or so we are told). As a result, systems and facilities in certain areas are experiencing “unfair” overload of resources. This raises several questions such as: How many PEH move to Washington state and over what time periods? What can we tell about geo movements of PEH, even within local (ish) communities, between different cities or counties? What are the characteristics of these PEH? What might cause relocations?

3. What can we look for and measure or learn regarding treatment stabilization? Is medication still changing over time or is it stable? What about the severity of conditions? At what point can we conclude that treatment was effective? What can we learn about durations and progress towards recovery?

4. What can we learn about ED/EU visits? Or visits to other facilities that imply acute episodes post stabilization? For example, say a person has post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and they are stabilized. If we see med adjustment at some point- what can we tell about triggering factors and follow-on outcomes? Take another example: If a stabilized person with bipolar disorder enters a manic state – what pressurized them?

5. For patients with history of high ED/EU utilization at one point in time – What can we learn by tracking their encounters from that point on? Has the frequency of ED/EU visits come down over time? What other behavioral health providers are linked to the person? What are the patterns of encounters with other providers and what are the correlations?

Selected references and resources

1. A. B. Chapman, K. Cordasco, S. Chassman, T. Panadero, D. Agans, N. Jackson, K. Clair, R. Nelson, A. E. Montgomery, J. Tsai, E.Finley, and S. Gabrielian, “Assessing longitudinal housing status using Electronic Health Record data: a comparison of natural language processing, structured data, and patient-reported history,” May 2023, Available: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/artificial-intelligence/articles/10.3389/frai.2023.1187501/full

2. Behavioral Health News, “Addressing Social Determinants of Health Among Individuals Experiencing Homelessness,” 2022. Available: https://behavioralhealthnews.org/addressing-social-determinants-of-health-among-individuals-experiencing-homelessness/

3. C. A. Marshall, “Effectiveness of employment‐based interventions for persons experiencing homelessness: A systematic review,” 2022. Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/hsc.13892

4. D. Polcin, “Co-occurring substance abuse and mental health problems among homeless persons: Suggestions for research and practice,” Aug. 2015, Available: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1179/1573658X15Y.0000000004

5. D. R. Harris, N. Anthony, D. Quesinberry and C. Delcher, “Evidence of housing instability identified by addresses, clinical notes, and diagnostic codes in a real-world population with substance use disorders,” Sep. 2023, Available: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-clinical-and-translational-science/article/evidence-of-housing-instability-identified-by-addresses-clinical-notes-and-diagnostic-codes-in-a-realworld-population-with-substance-use-disorders/B6F25107C9D2435730D1E3524A91D9A2

6. King County, “Substance use prevention and early intervention: Key steps to reduce harm and prevent use before it starts,” Jul. 2023, Available: https://publichealthinsider.com/2023/07/19/substance-use-prevention-and-early-intervention-key-steps-to-reduce-harm-and-prevent-use-before-it-starts/

7. L. A. Rodriguez, T. W. Thomas, H. Finertie, D. Wiley, W. T. Dyer, P. E. Sanchez, M. Y. , S. B. , A. Adams, and J. A. Schmittdiel, “Identifying Predictors of Homelessness Among Adults in a Large Integrated Health System in Northern California,” Mar. 2023, Available: https://www.thepermanentejournal.org/doi/10.7812/TPP/22.096

8. M. F. Shah, C. Black, and B. Felver, “Identifying Homeless and Unstably Housed DSHS Clients in Multiple Service Systems,” Apr. 2012, Available: https://www.dshs.wa.gov/ffa/rda/research-reports/identifying-homeless-and-unstably-housed-dshs-clients-multiple-service-systems

9. Minnesota Department of Human Services (DHS), “Adult mental health programs and services” and references therein, Available: https://mn.gov/dhs/people-we-serve/adults/health-care/mental-health/programs-services/

10. M. Liu and S. W. Hwang, “Health care for homeless people,” Ja. 2021, Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41572-020-00241-2

11. National Low Income Housing Coalition, “The Evidence Is Clear: Housing First Works,” 2021. Available: https://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/Housing-First-Evidence.pdf

12. P. Poremski, E. Whitley, and A. Lesage, “The Effect of Housing First Programs on Employment and Income of Homeless Individuals With Mental Illness,” 2016. Available: https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.ps.201500002

13. R. L. J. Thornton, C. M. Glover, C. W. Cené, D. C. Glik, J. A. Henderson, and D. R. Williams, “Evaluating Strategies For Reducing Health Disparities By Addressing The Social Determinants Of Health,” Aug. 2017, Available: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5524193/

14. R. Kuhn and D. P. Culhane, “Applying cluster analysis to test a typology of homelessness by pattern of shelter utilization: results from the analysis of administrative data,” Apr. 1998, Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9693690/

15. Revised Cost of Washington 43.185c, “Homeless Housing and Assistance,” Available: https://app.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=43.185C

16. S. A. Stella, R. Hanratty, A. J. Davidson, L. J. Podewils, L. Elliott, A. Keith, and R. Everhart, “Improving Identification of Patients Experiencing Homelessness in the Electronic Health Record: A Curated Registry Approach,” Dec. 2024, Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39285073/

17. S. Padgett, B. Henwood, and D. Stefancic, “Employment experiences of formerly homeless adults with serious mental illness: Qualitative findings,” Apr. 2020. Available: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7162698/

18. S. Schaffnit and T. Danielson, “Changing Support Needs Among Adults Experiencing Homelessness: Washington State Apple Health Clients, 2019-2023,” Aug. 2025, Available: https://www.dshs.wa.gov/rda-publication-categories/homelessness

19. S. Schaffnit and T. Danielson, “Health Service Utilization Among Apple Health Clients by Housing Status,” Apr. 2025, Available: https://www.dshs.wa.gov/ffa/rda/research-reports/health-service-utilization-among-apple-health-clients-housing-status

20. Technical Assistance Collaborative & Homelessness Strategic Initiatives, “The Role of Employment in Ending Homelessness,” Nov. 2023. Available: https://homelessstrategicinitiatives.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/TAC-OR-HSI-Supported-Employment-Report-FINAL-2023.pdf

21. United States Code 42 U.S.C. 119, “Homeless Assistance” and references therein, 2018, Available: https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2023-title42/USCODE-2023-title42-chap119

22. Urban Institute, D. A. Flaming, “Why It’s So Hard for People Experiencing Homelessness to ‘Just Get a Job,’” 2016. Available: https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/why-it-so-hard-people-experiencing-homelessness-just-go-get-job

23. Washington State Department of Social and Human Services (DSHS), “Cross-System Outcome Measures for Adults Enrolled in Medicaid” and references therein, 2013, Available: https://www.dshs.wa.gov/ffa/research-and-data-analysis/cross-system-outcome-measures-adults-enrolled-medicaid

24. Washington State Department of Social and Human Services (DSHS), “Measure Specification: Measure Attribution of Clients to Service Contracting Entities,” Available: https://www.dshs.wa.gov/ffa/research-and-data-analysis/measure-specifications

25. Washington State Fiscal Information, “A Citizen’s Guide to the Washington State Budget,” 2023, Available: https://fiscal.wa.gov/statebudgets/operatingbudgetmain and https://fiscal.wa.gov/PublicationsAndReports/2023%20Citizens%20Guide%20to%20Operating%20Budget.pdf

26. Washington State Health Care Authority (HCA), “Recommendations for Increasing Stable Housing in the Community Performance Measure Utilization,” Jul. 2024, Available: https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/program/increasing-stable-housing-measure-leg-report-2024.pdf